1.肺血栓塞栓症の臨床所見

臨床症状:

肺血栓塞栓症(PE)は多彩な臨床症状を呈するが、最も多いのは

「呼吸困難(73%)」、「胸痛(66%)」、「咳(37%)」である。

その他、起座呼吸(28%)、ふくらはぎor大腿の痛み(44%)、喘鳴(21%)、喀血(13%)が続く[1]。

さらに、10%以下の頻度で、AFなどの不整脈, 前失神, 失神、ショック、心停止、がある[2,3]。

大きな血栓によるPEでも症状が軽微ないしは無症状のことがある。無症状PEの真の発生率はわからないが、5233症例28研究のレビューでは全肺塞栓患者のうち1/3は無症状であった[4]。したがって、PEは何よりも「疑うことが」が重要である。

具体的に、あるメタアナリシスでは「担当医のインプレッション(主観)」の感度が85%、特異度が51%と高値であることが示された[5]。

肺動脈の中枢(主幹部や葉枝レベル)のPEであれば呼吸困難を来しやすい。対照的に末梢の枝のPEでは10%程度しか症状を示さない。末梢枝PEの症状としては胸膜炎による胸膜痛や、肺の出血性梗塞による喀血などがある。

複数のレトロ研究によると、失神で発症するPEは10%以下である。逆に失神患者のうち原因がPEだった割合は、リポートにもよるが2~17%とされている[6-12]。

身体所見:

頻呼吸(54%)、ふくらはぎや大腿のむくみ・紅斑・痛み・索状物などの変化(47%)、頻脈 (24%)、呼吸音の異常(減弱やラ音)(18%)、Ⅱ音の肺成分の増強(15%)、頸静脈の怒張 (14%)、発熱, 肺炎類似症状(3%)などがある。上肢DVT由来のPEは稀だが、上肢の痛みや張りといった症状があれば上肢由来のPEを疑う。

PE はショックや心停止の原因となる(8%)。とくに65歳以下で多い[13,14,15]。

このような患者では、発症直後から呼吸困難や頻呼吸を91%で認める。この場合、急性右心不全を呈するので、頸静脈の怒張、右寄りのⅢ音、チアノーゼなどを認める。

もともと肺高血圧がある患者では小さなPEでもショックに至る。経過において、例えば頻脈や徐脈を繰り返すことや, QRS幅が短時間で変化することは、右心に歪(ひずみ)が生じているサインでありPEを疑う。他に原因のはっきりしない右心負荷も必ずPEを疑う[16,17]。

検査所見:

PE患者の多くは血液ガスにて低酸素血症を呈する。低酸素血症(74%)、AADO2の開大(62~86%)、低炭酸ガス血症(41%)とされている[18]。

ただしPEの約18%は血液ガスの異常を呈さない[19]。通常、PEにおいて高炭酸ガス血症は認めないが、大きなPEで閉塞性ショックあるいは呼吸停止になった場合は、高炭酸ガス血症もあり得るので注意を要する。

トロポニンは心筋虚血のマーカーであるが、右心不全の際も上昇する。大きなPE患者の30~50%ではトロポニンが上昇し、予後の悪化と相関する[20,21]。PEにおけるトロポニンは約40時間で正常化する。これはAMIにおけるトロポニンの上昇は長時間持続するのと対照的である[22]。

PEにおいて心電図変化は頻発するが概ね非特異的である[23-27]。最も多い変化は頻脈と非特異的ST-T変化である(70%) [5]。以前から言われてきた心電図変化(S1Q3T3、右心負荷、IRBBBなど)の出現頻度は決して高くない(10%以下) [28]。

その他、心房性不整脈 (心房細動など)、徐脈(<50 bpm)、頻脈(>100 bpm)、新しいRBBB、下壁のQ波 (II, III, aVF)、前壁の陰性T波、S1Q3T3 パターンが出現した場合は、比較的予後不良のサインとされている[29]。

胸部レントゲンにおけるHampton’s hump(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hampton_hump)やWestermark’s(http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/115/8/e211/F1) サインは稀であるが、これらを認めたらPEを疑うべきである[30]。

Hampton’s hump isは末梢肺野に現れるコブ状の透過性低下域のことを指し、基部は胸膜側に、頂部は中枢に向く。 Westermark’sサインは肺血管の途絶影のことである。

2.アルゴリズムによる肺血栓塞栓症の診断

肺塞栓症はまず疑うことが大事である。そして肺塞栓症を疑ったら、ヒストリーや身体所見から、まず検査前確率(pretest probability:PTP)を判定する。PTPはWellsスコア(3階層)あるいは修正Wellsスコア(2階層)を用いる。Wellsスコアは以下の項目を含む:

- DVTを示唆する症状 (3点)

- PE以外に積極的に疑う疾患がない (3点)

- 心拍数 >100 (1.5点)

- 4週間以内に手術などで3日以上動かないことがあった(1.5点)

- DVT/PEの既往 (1.5点)

- 喀血 (1点)

- 悪性腫瘍あり(1点)

これらの項目から、低リスク(スコア=2点未満、中等度リスク(スコア2~6)、高リスク(スコア6.5以上)に分ける。WellsスコアはPEの疑われる外来患者に最も適している。

しかし入院患者でも、感度72%、特異度62 %というデータがあり[31]、さらに後述のようにDダイマーを加えることで、感度99%、特異度91 %に改善されるので入院患者にも利用可能である。

修正Wellsスコアはよりシンプルな2階層システムであり、全患者を①PE疑い例(5点以上)と②非疑い例(4点以下)に分ける。

このように2階層でも3階層でもよいが、3階層の方が後述のPERCや換気血流シンチと組み合わせてより効率的に利用可能なので[32-37]、ここでは3階層で論じることとする。

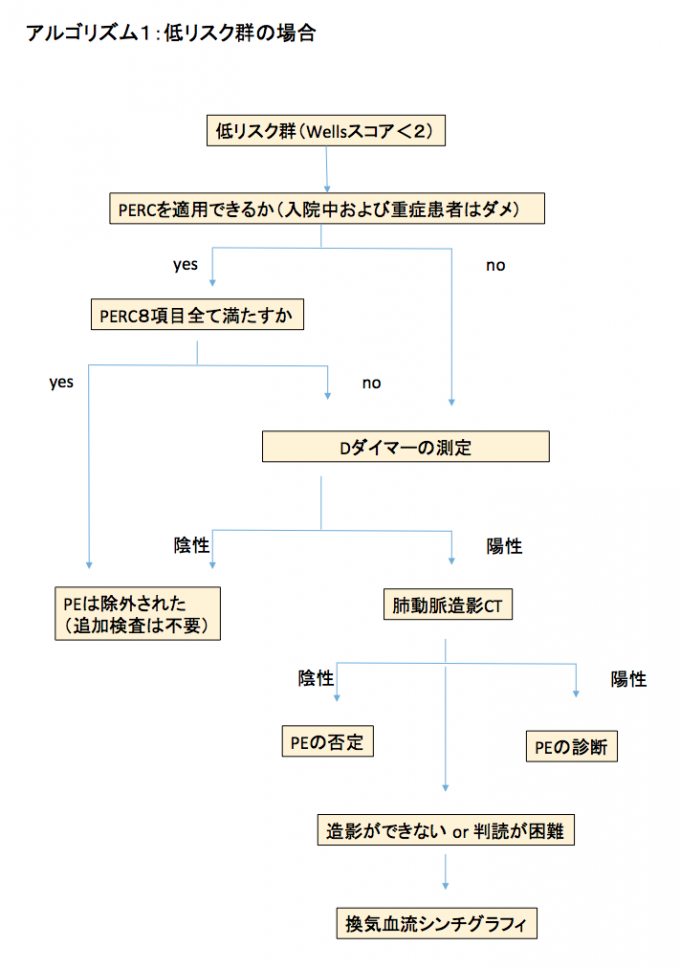

低リスク群:

検査前確率が低くWellsスコアが2点未満の低リスク群では、PE除外クライテリア(PE rule out criteria: PERC)を導入して、Dダイマーの測定が必要か否かを検討する(アルゴリズム1)。

すべての低リスク群患者にDダイマーを測定するという考えもあるが、PERCを用いることで、画像検査はもとよりDダイマーすら不要となる症例が約20%存在する[38]。PERCを導入した場合は下記のように考える;

- PERCの8項目すべてを満たす場合は、その後、いかなる検査も不要。

- 8項目中1項目でも満たした場合は、Dダイマー検査を行う。

PERCはPEの可能性が低い患者を検出して不要な検査の実施を抑制するためのものである[39-4-] PERCには8つの項目がある:

- 50歳未満

- 心拍数100未満

- SpO2=95以上

- 喀血がない

- エストロゲンを使っていない

- DVTやPEの既往がない

- 左右非対称の下肢浮腫がない

- 4週間以内に手術や外傷で入院したことがない

これら8項目全部満たせばPEである可能性が非常に低く(1%以下)、その先の検査を行う必要がない[39]。ただしPERCは元の検査前確率が低い場合にのみ利用可能である[40]。

さて、PERCが1項目でも陽性の場合や、PERCを導入できない患者(入院患者、重症患者など)は、Dダイマーを用いて以下のように考える[41]:

- Dダイマーが500 ng/mL未満の場合、その先の検査は不要

- Dダイマー500 ng/mL以上の場合肺動脈CTが必要

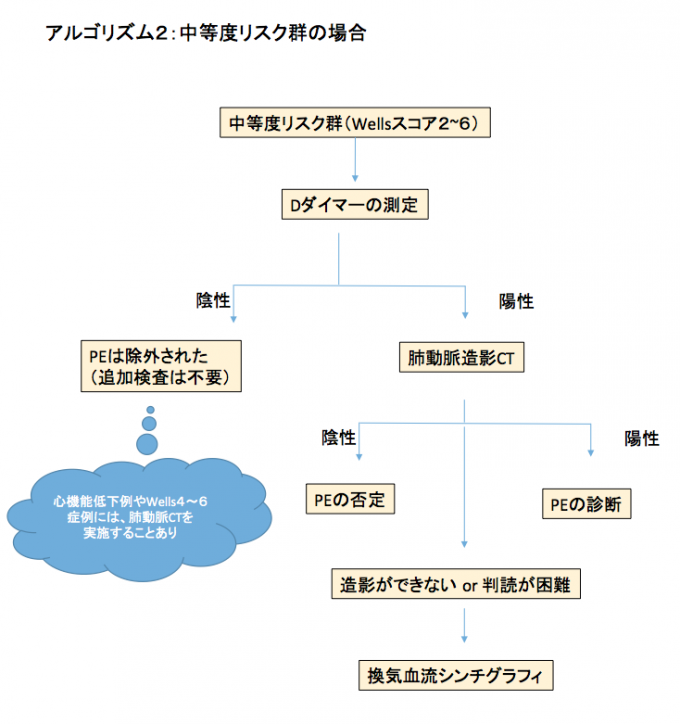

中等度リスク群:

中等度リスク患者の場合は、Dダイマーを測定するべきである(アルゴリズム2)。Dダイマーが500 ng/mL未満の場合, その先の画像撮影は不要である。

しかし患者によっては画像を取るべきとする見解もある。例えば心機能低下症例(PEによるダメージが大きい患者) 、中等度リスクのなかでも高リスクに近いレベル(Wellsスコアが4~6)の場合は念のために肺動脈CTを撮影することがある。

そしてDダイマーが500 ng/mL以上の場合は、画像を取るべきである。

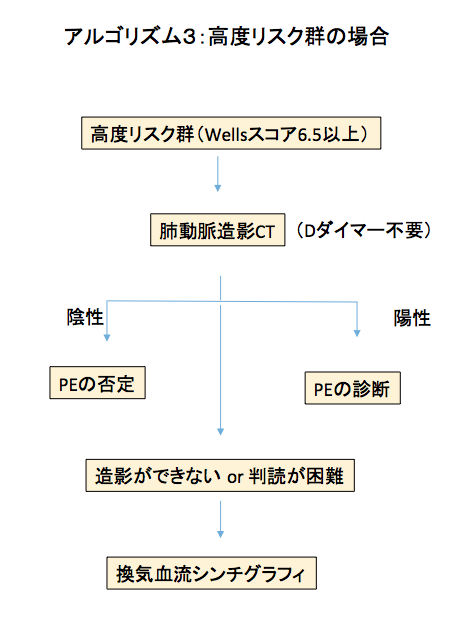

高リスク群:

高リスク患者の場合Dダイマーは参考にせず、肺動脈CTを撮影する(アルゴリズム3)。PEリスクが高いカテゴリーでは、Dダイマー陰性でもPEを否定できない。

たしかにDダイマー陰性はPEの可能性を下げるが、このカテゴリーのDダイマー陰性はPEの可能性を5%以下に下げることができない[42-46]。

肺動脈CTが禁忌の場合(アレルギー, 腎機能障害など)は、換気血流シンチを行う。また臨床的には高度にPEを疑うが肺動脈CTで明らかな塞栓を認めなかった場合に、次の画像検査手段として換気血流シンチを行う。

(文責:新井隆男)

◇◆◇

(参考文献)

1. Stein PD, Terrin ML, Hales CA, et al. Clinical, laboratory, roentgenographic, and electrocardiographic findings in patients with acute pulmonary embolism and no pre-existing cardiac or pulmonary disease. Chest 1991; 100:598.

2. Liesching T, O’Brien A. Significance of a syncopal event. Pulmonary embolism. Postgrad Med 2002; 111:19.

3. Castelli R, Tarsia P, Tantardini C, et al. Syncope in patients with pulmonary embolism: comparison between patients with syncope as the presenting symptom of pulmonary embolism and patients with pulmonary embolism without syncope. Vasc Med 2003; 8:257.

4. Stein PD, Matta F, Musani MH, Diaczok B. Silent pulmonary embolism in patients with deep venous thrombosis: a systematic review. Am J Med 2010; 123:426.

5. Lucassen W, Geersing GJ, Erkens PM, et al. Clinical decision rules for excluding pulmonary embolism: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2011; 155:448.

6. Blanc JJ, L’Her C, Touiza A, et al. Prospective evaluation and outcome of patients admitted for syncope over a 1 year period. Eur Heart J 2002; 23:815.

7. Soteriades ES, Evans JC, Larson MG, et al. Incidence and prognosis of syncope. N Engl J Med 2002; 347:878.

8. Vanbrabant P, Van Ouytsel V, Knockaert D, Gillet JB. Diagnostic yield of syncope investigation (initiated) in the emergency department: a pilot study. Acta Clin Belg 2011; 66:110.

9. Saravi M, Ahmadi Ahangar A, Hojati MM, et al. Etiology of syncope in hospitalized patients. Caspian J Intern Med 2015; 6:233.

10. Keller K, Beule J, Balzer JO, Dippold W. Syncope and collapse in acute pulmonary embolism. Am J Emerg Med 2016; 34:1251.

11. Prandoni P, Lensing AW, Prins MH, et al. Prevalence of Pulmonary Embolism among Patients Hospitalized for Syncope. N Engl J Med 2016; 375:1524.

12. Verma AA, Masoom H, Rawal S, et al. Pulmonary Embolism and Deep Venous Thrombosis in Patients Hospitalized With Syncope: A Multicenter Cross-sectional Study in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. JAMA Intern Med 2017; 177:1046.

13. Stein PD, Beemath A, Matta F, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with acute pulmonary embolism: data from PIOPED II. Am J Med 2007; 120:871.

14. Courtney DM, Sasser HC, Pincus CL, Kline JA. Pulseless electrical activity with witnessed arrest as a predictor of sudden death from massive pulmonary embolism in outpatients. Resuscitation 2001; 49:265.

15. Courtney DM, Kline JA. Prospective use of a clinical decision rule to identify pulmonary embolism as likely cause of outpatient cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2005; 65:57.

16. Guidelines on diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Task Force on Pulmonary Embolism, European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2000; 21:1301.

17. Kucher N, Goldhaber SZ. Management of massive pulmonary embolism. Circulation 2005; 112:e28.

18. Stein PD, Goldhaber SZ, Henry JW, Miller AC. Arterial blood gas analysis in the assessment of suspected acute pulmonary embolism. Chest 1996; 109:78.

19. Stein PD, Goldhaber SZ, Henry JW. Alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient in the assessment of acute pulmonary embolism. Chest 1995; 107:139.

20. Meyer T, Binder L, Hruska N, et al. Cardiac troponin I elevation in acute pulmonary embolism is associated with right ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 36:1632.

21. Horlander KT, Leeper KV. Troponin levels as a guide to treatment of pulmonary embolism. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2003; 9:374.

22. M?ller-Bardorff M, Weidtmann B, Giannitsis E, et al. Release kinetics of cardiac troponin T in survivors of confirmed severe pulmonary embolism. Clin Chem 2002; 48:673.

23. Geibel A, Zehender M, Kasper W, et al. Prognostic value of the ECG on admission in patients with acute major pulmonary embolism. Eur Respir J 2005; 25:843.

24. Ferrari E, Imbert A, Chevalier T, et al. The ECG in pulmonary embolism. Predictive value of negative T waves in precordial leads–80 case reports. Chest 1997; 111:537.

25. Rodger M, Makropoulos D, Turek M, et al. Diagnostic value of the electrocardiogram in suspected pulmonary embolism. Am J Cardiol 2000; 86:807.

26. Shopp JD, Stewart LK, Emmett TW, Kline JA. Findings From 12-lead Electrocardiography That Predict Circulatory Shock From Pulmonary Embolism: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med 2015; 22:1127.

27. Co I, Eilbert W, Chiganos T. New Electrocardiographic Changes in Patients Diagnosed with Pulmonary Embolism. J Emerg Med 2017; 52:280.

28. Panos RJ, Barish RA, Whye DW Jr, Groleau G. The electrocardiographic manifestations of pulmonary embolism. J Emerg Med 1988; 6:301.

29. Thames MD, Alpert JS, Dalen JE. Syncope in patients with pulmonary embolism. JAMA 1977; 238:2509.

30. Worsley DF, Alavi A, Aronchick JM, et al. Chest radiographic findings in patients with acute pulmonary embolism: observations from the PIOPED Study. Radiology 1993; 189:133.

31. Bass AR, Fields KG, Goto R, et al. Clinical Decision Rules for Pulmonary Embolism in Hospitalized Patients: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-analysis. Thromb Haemost 2017; 117:2176.

32. Le Gal G, Righini M, Roy PM, et al. Prediction of pulmonary embolism in the emergency department: the revised Geneva score. Ann Intern Med 2006; 144:165.

33. Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, et al. Derivation of a simple clinical model to categorize patients probability of pulmonary embolism: increasing the models utility with the SimpliRED D-dimer. Thromb Haemost 2000; 83:416.

34. Kline JA, Stubblefield WB. Clinician gestalt estimate of pretest probability for acute coronary syndrome and pulmonary embolism in patients with chest pain and dyspnea. Ann Emerg Med 2014; 63:275.

35. Schouten HJ, Geersing GJ, Oudega R, et al. Accuracy of the Wells clinical prediction rule for pulmonary embolism in older ambulatory adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014; 62:2136.

36. Hendriksen JM, Geersing GJ, Lucassen WA, et al. Diagnostic prediction models for suspected pulmonary embolism: systematic review and independent external validation in primary care. BMJ 2015; 351:h4438.

37. Hendriksen JM, Lucassen WA, Erkens PM, et al. Ruling Out Pulmonary Embolism in Primary Care: Comparison of the Diagnostic Performance of “Gestalt” and the Wells Rule. Ann Fam Med 2016; 14:227.

38. Kline JA, Courtney DM, Kabrhel C, et al. Prospective multicenter evaluation of the pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria. J Thromb Haemost 2008; 6:772.

39. Hugli O, Righini M, Le Gal G, et al. The pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria (PERC) rule does not safely exclude pulmonary embolism. J Thromb Haemost 2011; 9:300.

40. Singh B, Mommer SK, Erwin PJ, et al. Pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria (PERC) in pulmonary embolism–revisited: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Emerg Med J 2013; 30:701.

41. Le Gal G, Righini M, Roy PM, et al. Value of D-dimer testing for the exclusion of pulmonary embolism in patients with previous venous thromboembolism. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166:176.

42. Stein PD, Hull RD, Patel KC, et al. D-dimer for the exclusion of acute venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2004; 140:589.

43. Stein PD, Woodard PK, Weg JG, et al. Diagnostic pathways in acute pulmonary embolism: recommendations of the PIOPED II investigators. Am J Med 2006; 119:1048.

44. Kearon C, Ginsberg JS, Douketis J, et al. An evaluation of D-dimer in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2006; 144:812.

45. Righini M, Le Gal G, Aujesky D, et al. Diagnosis of pulmonary embolism by multidetector CT alone or combined with venous ultrasonography of the leg: a randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2008; 371:1343.

46. Crawford F, Andras A, Welch K, et al. D-dimer test for excluding the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; :CD010864.

救急科専門研修

救急科専門研修 見学・お問い合わせ

見学・お問い合わせ